The Slow Cancellation of Innovation: A critical look at modern funding

Guest article by Aishwarya Khanduja

Aishwarya is a curiosity-driven systems thinker working at the intersection of technology and society. Her interests span human-AI collaboration, social technology, knowledge systems, and complex adaptive systems.

A biotech and edtech builder, she’s now leading Analogue, an R&D fund creating space for unconventional innovators and breakthrough ideas. (submit an idea!)

“In conditions of [digital] recall, loss is itself lost.” – Mark Fisher

In 2014, cultural theorist Mark Fisher published a seminal essay The Slow Cancellation of the Future, describing a peculiar temporal1 paralysis gripping contemporary culture. Fisher observed that despite rapid technological advancement, cultural production had become trapped in a loop of nostalgia and recycled forms, unable to generate genuinely new possibilities. Where previous decades had been marked by distinct musical and cultural innovations, the 21st century seemed caught in an endless cycle of retrospection, remixing past styles rather than creating novel ones. This condition, which Fisher termed “hauntology,” described a present haunted by the ghosts of lost futures - possibilities once imagined but never realized.

A decade later, Fisher's observation about cultural stagnation finds an unexpected parallel in the world of innovation funding. Just as popular culture became trapped in cycles of reproduction rather than creation, the institutions responsible for funding scientific and technological progress appear increasingly bound by their own forms of temporal paralysis. The venture capital industry, government funding bodies, and research institutions – originally designed to fuel breakthrough innovation – have gradually oriented themselves toward preserving existing power structures and paradigms rather than enabling new ones. Where once these institutions served as engines of radical innovation, they now frequently function as guardians of incremental improvement, haunted by their own past successes while struggling to imagine or enable truly novel futures.

This piece examines how the “slow cancellation of the future” manifests in our innovation funding systems. Through analysis of venture capital trends, research grant distributions, and institutional incentives, we can observe patterns that mirror Fisher's cultural critique: a systematic bias toward the familiar, a growing temporal disjunction between innovation and funding structures, and most crucially, the gradual disappearance of spaces for genuine novelty. Just as Fisher identified how cultural institutions had become trapped in cycles of nostalgic reproduction, we find our innovation funding mechanisms increasingly caught in self-reinforcing patterns that prioritize preservation over progress, safety over disruption, and institutional stability over transformative change.

The implications of this parallel extend far beyond simple institutional critique. If Fisher was right that cultural stagnation reflected deeper problems in our society's relationship with time and possibility, then the similar patterns emerging in innovation funding suggest a broader crisis in how we imagine and enable futures. Understanding this crisis - and finding ways to address it - may be crucial not just for the future of innovation funding, but for our collective ability to imagine and create new possibilities in an age of mounting global challenges.

To be clear, the existence of breakthrough technologies and continued scientific progress is undeniable - from mRNA vaccines to large language models, from CRISPR to renewable energy advances. Individual scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs continue to push boundaries and achieve remarkable breakthroughs. Yet this observation makes the systemic problem even more striking: these advances emerge despite our funding structures, not because of them. The rate and distribution of innovation suggest that our current systems capture only a fraction of our creative potential. When we examine who gets to innovate, when they get to innovate, and what types of innovation receive support; a troubling pattern emerges. We are systematically underutilizing our collective capacity for discovery and transformation at precisely the moment when we most need to accelerate it. Our own funding mechanisms have become a bottleneck rather than a catalyst - and recognizing this is the first step toward reimagining them.

The Temporal Crisis in Academic Scientific Funding

Nowhere is the slow cancellation of the future more starkly visible than in the changing demographics of scientific funding. The NIH's own data tells a story of systematic temporal stagnation: where in 1980 over 18% of principal investigators were under 35, by 2014 that number had plummeted to barely 2%. Meanwhile, the proportion of researchers over 66 has risen steadily, creating a striking inversion in the age distribution of funded researchers. This is not merely a demographic shift - it represents a fundamental restructuring of how we allocate resources for scientific discovery.

This temporal distortion becomes even more apparent when we examine the age at which researchers receive their first R01 grant - traditionally considered the first major milestone of an independent scientific career. The distribution has shifted dramatically rightward over the past 25 years, with the modal age of first grant receipt moving from the mid-30s to the mid-40s. While this partly reflects broader demographic trends, it signifies something more profound: a growing misalignment between our funding institutions and the natural rhythms of scientific discovery.

Historical analysis suggests that many breakthrough scientific discoveries come from researchers in their 20s and early 30s — the very demographic our current system increasingly excludes.2 This creates what we might call, borrowing Fisher's terminology, a form of institutional hauntology: our funding mechanisms are haunted by an idealized past of ‘seasoned researchers,’ while systematically failing to create space for the kind of youthful innovation that characterized many historic breakthroughs.

The Venture Capital Paradox: More Capital, Less Innovation

The venture capital industry presents a striking parallel to the NIH's temporal crisis, albeit with its own peculiar contradictions. At first glance, the raw numbers suggest abundance rather than scarcity — as Bruce Booth notes, there is “10x more VC money available today than a decade ago.” Yet this surface-level abundance masks a deeper form of temporal paralysis, one that manifests in what we might call the venture capital paradox: more capital has led to less innovation, not more.

This paradox becomes visible in the industry's structural evolution. Recent data shows VC funding has plummeted back to 2018 levels, with new venture capitalists being hit hardest – first-time fund managers saw their fundraising drop from over $20 billion in 2022 to just $4 billion in 2024. This isn't merely a cyclical downturn but rather, again, represents institutional hauntology: the industry has become haunted by its own past successes, increasingly allocating capital based on historical patterns rather than future possibilities.

The concentration of capital tells its own story. The top 30 firms raised $49 billion, while 188 emerging firms collectively raised just $9.1 billion. This consolidation3 creates what Booth describes as a "mega-round" phenomenon that “promotes capital inefficiency, reduces marginal pipeline quality, and constrains viable exit paths.”

In Fisher's terms, we might say the industry has created its own form of temporal lock-in, where past success becomes the primary predictor of future investment, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that makes genuinely novel approaches increasingly difficult to fund.

This temporal distortion manifests in what might be called the “venture feedback arbitrage” - a structural problem that goes beyond the commonly discussed lag between investment and outcome.

The venture capital process can be understood as two distinct reinforcement learning systems:

for identifying opportunities

for deploying capital and supporting investments

While the latter system suffers from classic temporal dislocation - with 7-10 year lags between action and result creating a “temporal credit assignment problem” - the former system has evolved its own problematic feedback loops.

In early-stage venture sourcing, firms have developed what appears to be a more tractable system of intermediate rewards: reputation building, network effects, and competitive access to deals. Yet this very tractability may contribute to the industry's temporal paralysis.

By optimizing for these shorter-term, measurable signals - what vg calls “dense intermediate rewards” - venture firms risk creating another form of hauntological trap, where the metrics of previous success become self-reinforcing barriers to genuine innovation – much like how local optima can prevent discovery of global maxima.

The most sophisticated firms attempt to navigate this through careful instrumentation of their sourcing and decision processes, tracking causal chains from initial actions through network effects to deal flow. However, this very sophistication - the attempt to decompose venture capital into “separable components with different temporal structures” - may paradoxically contribute to the industry's growing conservatism. As Fisher observed in cultural production, the drive to make processes more predictable and measurable can lead to a system that prioritizes the reproduction of past patterns over the emergence of genuine novelty.

This sophistication paradox is further complicated by the industry's shifting capital base. As Nichole Wischoff observes, while fund sizes have “ballooned into the many billions,” many leading firms have lost over 20% of their traditional limited partner base, forcing them to spend “a ton of time in the Middle East” seeking sovereign wealth replacements. This geographic and institutional shift in capital sources represents another form of temporal distortion - as established firms become increasingly dependent on sources of capital with their own distinct time horizons and priorities, the industry's ability to support genuinely novel innovation may be further constrained.

The Double Bind of Innovation Funding

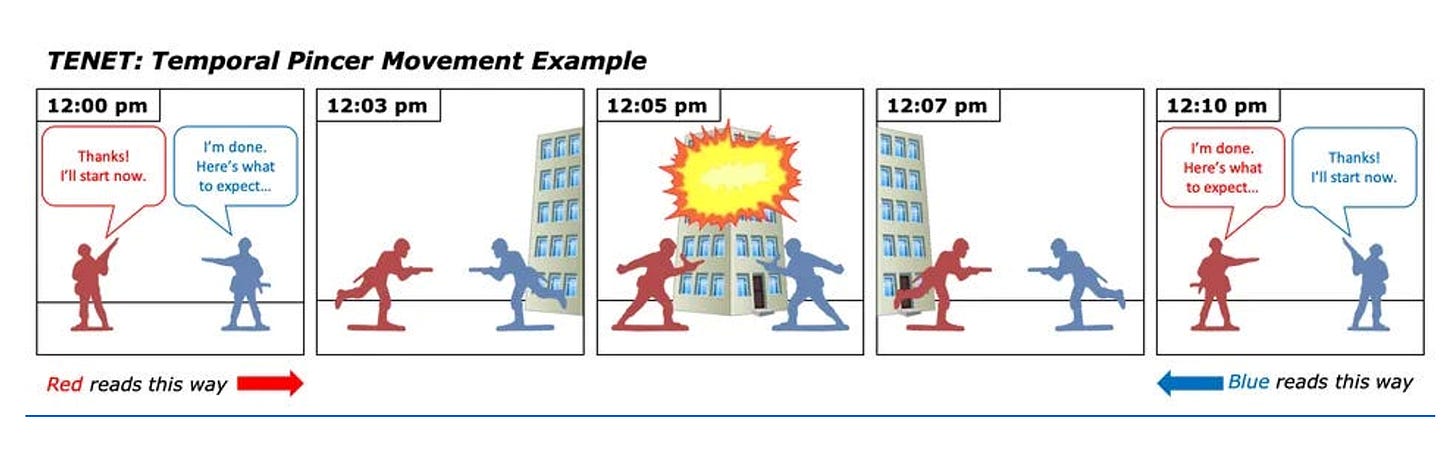

When we examine these venture capital dynamics alongside the NIH funding patterns discussed earlier, a troubling picture emerges - a “double bind” for novel research and innovation. Young scientists face increasingly lengthy paths to their first grants, with the median age of first R01 recipients creeping steadily upward, while young venture capital firms struggle to raise their first funds, with new manager fundraising plummeting from $20 billion to $4 billion in just two years. This creates a form of temporal pincer movement4 against innovation: the institutional structures meant to support new ideas have simultaneously aged at both ends of the pipeline.

This pincer effect is particularly devastating for late bloomers,5 who face not just institutional barriers but a fundamental temporal mismatch between their chronological age and professional trajectory.

This double bind operates through parallel mechanisms of temporal distortion.

In academic science, the shift toward older investigators reflects “institutional hauntology” - a system haunted by an idealized past of established researchers, gradually closing off pathways for younger scientists who historically drove many breakthrough discoveries.

In venture capital, we see a mirror image of this process, where the concentration of capital in established firms creates its own form of temporal lock-in, making it increasingly difficult for new managers to emerge with fresh perspectives and approaches.

The result is a kind of systemic sclerosis in the innovation funding landscape. Just as Fisher observed culture becoming trapped in cycles of nostalgic reproduction, our mechanisms for funding scientific and technological progress have become caught in self-reinforcing patterns that prioritize the familiar over the novel, the established over the emerging. The very institutions designed to enable future possibilities have become, “haunted by futures that failed to happen.”

Implications: The Lost Generation of Innovation

This double bind creates particularly acute challenges in fields requiring both significant scientific advancement and sustained capital investment - areas like biotechnology, clean energy, and advanced materials. These domains, which often require a decade or more to move from scientific breakthrough to commercial viability, are especially vulnerable to the temporal distortions we've identified.

Consider biotechnology, where the pincer movement of aging grant recipients and conservative venture capital creates multiple barriers to innovation. Young scientists with novel approaches to therapeutic development face a triple challenge: they must wait longer for independent research funding, they struggle to find venture capital willing to take early risks, and when they do find funding, it increasingly comes with pressure to pursue incremental improvements rather than paradigm-shifting approaches. This dynamic helps explain why, despite enormous capital flowing into the sector, many fundamental challenges in drug development remain unsolved while investment clusters around proven approaches and established modalities.

The clean energy sector offers another telling example. The urgency of climate change demands radical innovation in energy generation, storage, and distribution. Yet our funding systems' temporal distortions create a systematic bias toward incremental improvements to existing technologies rather than supporting potentially transformative approaches. Young researchers proposing novel approaches to fusion energy or next-generation solar technology face the same stretched timelines for grants, while venture capital's emphasis on shorter-term metrics makes it increasingly difficult to fund the kind of decade-long development cycles such innovations require.6

This temporal misalignment creates a "lost generation" of potential innovations - ideas that never materialize not because they lack merit, but because they fall into the growing gaps between our funding institutions' distorted time horizons. Just as Fisher observed culture losing its ability to imagine and create new futures, our innovation funding systems may be losing their ability to nurture truly transformative ideas, particularly those requiring both scientific breakthrough and sustained capital investment.

New Models and Their Limits: Attempting to "Uncancel" the Future

The response to this systemic sclerosis reveals a deeper paradox: while new funding and R&D organizations are emerging to restore healthier temporal rhythms to innovation, most end up reproducing the very barriers they aim to dissolve. Current "alternative" funding models - whether research institutes, focused research organizations, or scientific venture studios - still largely operate within the confines of traditional credentialing and institutional networks. They may offer new funding mechanisms, but they rarely challenge the fundamental assumptions about who can contribute to innovation.

This challenge manifests across the entire innovation pipeline, from basic research through commercialization. In fundamental science, we need funding structures that protect the long time horizons and intellectual freedom required for deep exploration while remaining open to insights from unexpected sources. At the translational level, we need new models for bridging theoretical understanding with practical knowledge. And in venture capital, we need mechanisms that can recognize and support breakthrough ideas before they fit neatly into existing patterns of success.

Consider what remains systematically excluded: the machinist who develops novel insights into materials science through decades of hands-on experience, the kid who solves electricity for his village in Malawi, the small-town plumber who intuits breakthrough approaches to fluid dynamics. These perspectives - grounded in direct engagement with physical and social reality - are precisely the kind of thinking our innovation systems claim to seek. Yet our funding structures, even the supposedly alternative ones, continue to filter them out through credentialist requirements and institutional gate-keeping.

History offers compelling evidence of this loss. For example, Frank Zybach, a Colorado farmer with no high school diploma, reimagined agriculture by inventing the center pivot irrigation system in the 1940s. His daily observations of water patterns led to insights that trained engineers had missed. Similarly, Julian Kindred, a machinist at UT Austin's physics department, developed crucial vacuum chamber techniques in the 1960s that advanced particle physics research, despite having no formal physics education. His hands-on understanding of metals under extreme conditions surpassed contemporary materials science knowledge.

This exclusion represents a "double hauntology" - our institutions are haunted not only by the futures they failed to create, but by the potential innovators they failed to recognize. The very metrics we use to identify promising ideas - academic credentials, institutional affiliations, track records of traditional success - systematically filter out the novel perspectives that might generate genuine breakthroughs.

The meta-temporal challenge, then, becomes multi-layered: How do we create funding structures that can support both the patient, open-ended exploration needed for fundamental discovery and the rapid iteration required for practical innovation? How do we recognize and nurture raw talent and insight wherever it appears? This requires more than just new funding mechanisms - it demands new ways of identifying, evaluating, and supporting innovation at every stage of development.

Some nascent efforts point toward possible futures. Imagine funding structures that operate like talent scouts in sports, actively seeking out promising thinkers regardless of background. Or "innovation syndicates" that allow independent researchers to pool resources and knowledge outside institutional frameworks. Or "pre-seed research funding" that supports individual exploration before ideas are fully formed enough for traditional evaluation. These models could work alongside traditional academic institutions and venture capital, creating multiple pathways for ideas to develop and mature.

Yet even these potential models face Fisher's fundamental challenge: how to create genuinely new possibilities while operating within existing systems. The temporal translation problem isn't just between different time horizons, but between different ways of recognizing and valuing innovation itself. Creating truly open pathways for innovation may require us to first innovate in how we see innovation - to uncancel not just the future, but our ability to recognize who might create it.

Beyond Reform: Reimagining Innovation Time and Its Creators

The challenges we've identified reveal a double haunting of innovation: we are haunted not just by futures unrealized, but by voices unheard. If Fisher's analysis of cultural stagnation teaches us anything, it's that temporal distortions reflect deeper structural conditions - they manifest not only in when innovation happens, but in who gets to innovate. The question becomes how to reimagine both our relationship with innovation time and our understanding of who shapes it.

This reimagining requires us to confront several interwoven paradoxes. While our problems manifest in institutional structures - aging grant recipients, concentrated venture capital, extended feedback loops - their roots lie in a deeper double bind. Our metrics and processes, designed to make innovation more "predictable," have created what Fisher might have called a "bureaucratization of time" that systematically favors not only the familiar over the novel, but the credentialed over the experienced. The machinist's decades of hands-on insight operates in a different temporal register than the PhD researcher's theoretical framework, yet our institutions can only recognize and value one of these temporal modes.

Any attempt to restore healthier temporal rhythms must therefore work on two levels simultaneously. It must create space for different time horizons - from quick iterations to patient breakthroughs - while also forming space for different ways of knowing and building that operate on their own temporal logic. A plumber's intuitive understanding of fluid dynamics emerges through years of practical engagement that follows very different rhythms than academic research. Our challenge is not just to bridge different time horizons, but to recognize and value these different temporal experiences of innovation.

The emergence of new funding models like Arc Institute and New Science points toward one possible path: the creation of what we might call "temporal-experiential refuges" – protected spaces where innovation can proceed according to both its natural rhythms and its natural creators rather than institutional imperatives. These spaces must be designed to recognize and nurture talent wherever it emerges, understanding that innovation's temporality is inseparable from the diverse experiences that generate it.

This suggests the need for what we might call a practice of "inclusive temporal design" in innovation funding. Rather than treating time as a neutral container, we must actively shape temporal structures that can recognize and support multiple ways of knowing and creating. This could involve:

Creating funding mechanisms that explicitly value both temporal and experiential diversity - supporting different modes of innovation that emerge from different life experiences

Developing new metrics that measure not just innovation's relationship with time, but how different forms of expertise and experience generate their own temporal patterns

Building institutions that can recognize and nurture talent across multiple temporal and experiential registers

Finding ways to value and protect both "slow time" and "practical time" - the extended periods needed for both theoretical insight and hands-on mastery

Most fundamentally, we must restore what Fisher called "the future as virtuality" by expanding our understanding of who can create that future. This requires more than institutional reform; it requires rebuilding our collective capacity to recognize and value innovation potential in all its forms. The temporal translation problem is inseparable from the recognition problem - we cannot reimagine innovation time without reimagining who gets to shape it.

The stakes could not be higher. In an age of mounting global challenges, our ability to generate genuinely novel solutions may depend on our capacity to recognize and nurture innovation potential wherever it exists. The slow cancellation of innovation is not just about lost futures - it's about lost innovators. Understanding and addressing both dimensions of this haunting may be crucial not just for the future of innovation funding, but for our ability to create a future that draws on humanity's full creative potential.

Glossary

Theoretical Frameworks

Hauntology A concept developed by Mark Fisher describing how the present is haunted by "lost futures" - possibilities that were once imagined but never materialized. In the context of innovation funding, it describes how past models of success continue to shape and constrain current possibilities.

Institutional Hauntology The specific way funding institutions become trapped by their own past successes, creating systems that prioritize reproducing established patterns rather than enabling genuine innovation. Manifests in practices like favoring older researchers or established firms.

Temporal Paralysis A condition where institutions lose their ability to generate genuinely new possibilities, instead becoming trapped in cycles of reproducing past patterns. In innovation funding, this appears as the systematic preference for "proven" approaches over novel ones.

Funding Mechanics

R01 Grant The primary research grant mechanism used by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), traditionally considered the first major milestone of an independent scientific career. The increasing age at first R01 receipt (from mid-30s to mid-40s) represents a key indicator of temporal distortion in academic funding.

Venture Feedback Arbitrage A structural problem where venture capital firms optimize for shorter-term, measurable signals (like reputation and deal flow) rather than long-term innovation potential, creating self-reinforcing barriers to novel approaches.

Dense Intermediate Rewards Short-term, measurable metrics in venture capital (such as network effects or deal access) that can be optimized for, potentially at the expense of supporting genuinely novel innovation.

Temporal Concepts

Temporal Pincer Movement A dual compression of innovation opportunities where both academic funding and venture capital have simultaneously aged at opposite ends of the pipeline. Named after the military maneuver of attacking from two directions simultaneously.

Temporal Phase Mismatch The specific predicament faced by late bloomers, where their chronological age conflicts with institutional expectations about career progression and expertise accumulation. Creates situations where individuals are simultaneously "too old" and "too young" for different opportunities.

Temporal Credit Assignment Problem The challenge in venture capital of connecting actions to outcomes across long time horizons (typically 7-10 years), making it difficult to optimize decision-making processes.

Emerging Solutions

Temporal-Experiential Refuges Protected spaces designed to allow innovation to proceed according to its natural rhythms rather than institutional imperatives. Examples include new funding models like Arc Institute and New Science.

Inclusive Temporal Design An approach to creating funding structures that explicitly accounts for and supports different temporal experiences of innovation, from rapid iteration to long-term exploration.

Industry Terms

Mega-Round Phenomenon The trend toward increasingly large funding rounds in venture capital, which can promote capital inefficiency and reduce opportunities for novel approaches.

First-Time Fund Managers Venture capitalists raising their first fund, whose declining success in fundraising (from $20B to $4B) represents another aspect of the system's bias toward established players.

Focused Research Organizations (FROs) A new institutional model attempting to bridge the gap between academic research and practical innovation, though often still constrained by traditional credentialing requirements.

The term "temporal" in this essay refers to relationships with and experiences of time itself. When we describe "temporal paralysis" or "temporal distortion" in innovation funding, we're identifying specific ways that the normal flow of time—from past through present to an open future—becomes disrupted.

In healthy innovation systems, time flows naturally: new ideas emerge from new people, past success informs but doesn't overdetermine future opportunity, and the future remains open to genuine novelty. However, in systems experiencing temporal distortion, this flow breaks down: the past begins to dominate the future (as when funding increasingly concentrates in established hands), time horizons stretch abnormally (as when the age of first grant receipt creeps from 35 to 45), and feedback cycles extend beyond useful lengths (as with venture capital's 7-10 year return horizons).

This creates what Fisher called “temporal paralysis”—a condition where the future becomes more like a replay of the past than a space of genuine possibility. This distorted relationship with time manifests concretely in everything from career trajectories to funding decisions to institutional structures.

To be sure, this phenomenon may partly represent the aging of the Baby Boomer generation, in that they were roughly 30 years old in 1980 (when winning a federal grant was far easier) and have often continued to run labs until today (given the fact that there is no forced retirement). But it also signifies a huge disconnect from the reality of scientific breakthroughs, which often occur from people in their 20s if not earlier.

A tweet by Matt Parlmer inspired this section: “This sector of finance is either way too consolidated or not nearly consolidated enough.”

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation. This classic maneuver has been important throughout the history of warfare

Temporal Pincer in Tenet

Christopher Nolan's TENET reimagines this tactic through time itself, with teams operating in opposite temporal directions to create a coordinated "temporal pincer."

This cinematic concept provides an unexpectedly apt metaphor for the crisis facing late-career innovators in today's funding landscape. Just as TENET's temporal pincer creates a devastating squeeze from opposing time directions, late bloomers face a similar compression from two temporal fronts: from the "forward" direction, venture capital has advanced toward later-stage investments, demanding increasingly substantial proof of success even at seed stage—a dramatic shift from the historical willingness to fund speculative early-stage innovations. From the "backward" direction, academic funding has retreated toward established researchers with extensive publication records.

For late bloomers, this traditional pincer movement becomes even more complex because they face a second temporal paradox overlaid on top of the first. Imagine someone switching careers into technology at 35. They encounter what we might call a "temporal phase mismatch" where they're caught between two incompatible timelines:

Chronological Timeline: They're considered "too old" for opportunities designed for young innovators. Many accelerators, fellowships, and early-career grants have explicit age restrictions or "years since degree" requirements that automatically exclude them.

Professional Timeline: Despite their chronological age, they're viewed as "too young" in terms of domain expertise. The system expects someone their age to have accumulated decades of relevant experience, creating a mismatch between their actual career stage and what's expected for their age cohort.

This creates an interesting parallel to TENET's temporal mechanics: Just as objects in TENET can experience time differently from their surroundings, late bloomers exist in a state of temporal contradiction. Their chronological age moves forward while their professional experience is judged against a backwards-moving standard of expectations, which adds an added layer of complexity.

While helping edit this piece, Stuart Buck pointed out that Breakthrough Energy is an example of wealthy people funding long term tech projects that have societal benefits when traditional VC was not willing to do so.

This is a fascinating post – thanks for writing. I think there’s a lot of truth in the argument. It’s consistent with other pieces I’ve seen and my own prior experience as an academic. However, I think the argument still lacks power because of the difficulty in quantifying the extent of the problem.

You rightly point out the slow rise in the age at which PI’s get their first NIH R01 grant (rising from a mean of 37 in 1995 to 41 in 2020 according to my squinting at your graph) and the striking decline in new VC funding. But elsewhere you write things like: “the existence of breakthrough technologies and continued scientific progress is undeniable - from mRNA vaccines to large language models, from CRISPR to renewable energy advances. Individual scientists, engineers, and entrepreneurs continue to push boundaries and achieve remarkable breakthroughs. Yet this observation makes the systemic problem even more striking: these advances emerge despite our funding structures, not because of them.” I’m sure that’s true to some extent but how much? To take CRISPR as just one example, my guess would be that Jennifer Doudna, one of the leading lights in this field, has been well supported by the NIH.

And while I agree with you that “the drive to make processes more predictable and measurable can lead to a system that prioritizes the reproduction of past patterns over the emergence of genuine novelty”, again I wonder how do we quantify that effect? Can we? The risk of propagating this kind of stagnation seems to be likely to grow as funders start to apply AI to analyse the outcomes of prior decision making.

Finally, I also agree that we need to “innovate in how we see innovation”, but how do we do that exactly? Does it not take us back to the perennial problem of persuading funders and researchers to take risks – and then properly assessing the yield from that risk-taking?

Sorry for all the questions. I do think this is a genuinely important and difficult problem. While one can try to diagnose general problems with 'the system', I'm interested in how we get to the root of those problems (which likely operate in different parts of the system) with the clarity needed to plan and test some kinds of intervention.