Unbundling the University, Part 3

by Ben Reinhardt

This is part 3 of Ben Reinhardt’s monograph on Unbundling the University. For the first two parts, see here and here. For more of Ben’s work, check out the Speculative Technologies site.

2. Universities have been accumulating roles for hundreds of years

Or, disgustingly abbreviated history of the modern university with a special focus on research and the creation of new knowledge and technology.

Medieval Universities

The first universities emerged in the 12th century to train clergy, who needed to be literate (at least in Latin) and have some idea about theology. Institutions of higher education had existed before, and academia arguably predates Socrates, but we can trace our modern institutions back to these medieval scholastic guilds in places like Paris, Bologna, and Oxford. In a recognizable pattern, the types of people who became professors also were the type of person who also liked trying to figure out how the world worked and arguing about philosophy. Many of the people who became clergy were the second sons of noblemen, who quickly realized that learning to read and a smattering of philosophy was useful. Nobles started sending their other children to universities to learn as well.

So from the start, you have this bundle of vocational training (although very scoped), general skills training, moral instruction, and inquiry into the nature of the universe. The business model was straightforward: donations paid for the original structures, and then students paid instructors directly; there were a small number of endowed positions whose salaries weren’t tied to teaching.

Also from the start, university professors spent a lot of time trying to come up with new ideas about the world; however, ‘natural philosophy’ – what we would now call science – was just a small fraction of that work. “How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?” was as legitimate a research question as “why does light create a rainbow when it goes through a prism?” There was no sense that these questions had any bearing on practical life or should be interesting to anybody besides other philosophers. This thread of “academia = pure ideas about philosophy and the truth of how the world works” remains incredibly strong throughout the university story. The centrality of ideas and philosophical roots created another strong thread that we will see later: the deep importance of who came up with an idea first.

The result of this setup was that professors were incentivized to teach well enough to get paid (unless they had an endowed chair) and create ideas that impress other professors. Academia has always been the game where you gain status by getting attention for new knowledge.

Early Modern Universities

The tight coupling between academia and pure ideas meant that when the idea of empiricism (that is, you should observe things and even do experiments) started to creep into natural philosophy in the 17th century, much of the work that we would now call “scientific research” happened outside of universities. Creating new technology was even further beyond the pale. Maybe less than a quarter of the Royal Society of London were associated with the university when it was first formed.

(Side note: the terms “science” and “scientist” didn’t exist until the 19th century so I will stick with the term “natural philosophy” until then.)

While a lot of natural philosophy was done outside of universities, the people doing natural philosophy still aspired to be academics. They were concerned with philosophy (remember, natural philosophers!) and discovering truths of the universe.

The creation of the Royal society in 1660 and empiricism more broadly also birthed the twin phenomena of:

Research becoming expensive: now that research involved more than just sitting around and thinking, natural philosophers needed funding beyond just living living expenses. They needed funding to hire assistants, build experiments, and procure consumable materials. Materials which, in the case of alchemy, could be quite pricey.

Researchers justifying their work to wealthy non-technical patrons in order to get that funding. The King was basically a philanthropist and the government fused into one person at this point.

Research papers were invented in the 17th century as well and had several purposes:

A way for researchers to know what other researchers were doing. (Note that these papers were in no way meant for public consumption).

A way for researchers to claim primacy over an idea. (Remember, the game is to be the first person to come up with a new idea!)

A way to get researchers to share intermediate results. Without the incentive of the paper, people would keep all their findings to themselves until they could create a massive groundbreaking book. Not infrequently, a researcher would die before he could create this magnum opus.

During the early modern period, while natural philosophy made great leaps and bounds, the university’s role and business model didn’t change much: it was still primarily focused on training clergy and teaching philosophy and the arts to young aristocrats. While some scientific researchers were affiliated with universities (Newton famously held the Lucasian Chair of Mathematics which paid his salary independent of teaching) the majority did not. Isaac Newton became a professor mostly as a way to have his living costs covered while doing relatively little work — he lectured but wasn’t particularly good at it. Professors being in a role that is notionally about teaching but instead spending most of their energy doing research instead and being terrible teachers is a tradition that continues to this day.

19th century

The medieval model of the university continued until the 19th century ushered in dramatic changes in the roles and structure of the university. Universities shifted from being effectively an arm of the church to an arm of the state focused primarily on disseminating knowledge and creating the skilled workforce needed for effective bureaucracies, powerful militaries, and strong economies. The 19th century also saw the invention of the research university -- taking on its distinctly modern role as a center of research.

During the 19th century the vast majority of Europe organized itself into nation-states. Everybody now knew that science (which had clearly become its own thing, separate from philosophy) and arts (which at this point included what we would now call engineering) were clearly coupled to the military and economic fates of these nation-states: from the marine chronometer enabling the British navy to know where it was anywhere in the world, to growing and discovering nitre for creating gunpowder, to the looms and other inventions that drove the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. However, at the beginning of the 19th century, most of this work was not happening at universities!

Universities at the beginning of the 19th century looked almost the same as they did during the medieval and early modern period: relatively small-scale educational institutions focused on vocational training for priests and moral/arts instruction for aristocrats. However, modern nation-states needed a legion of competent administrators 2 to staff their new bureaucracies that did many more jobs than previous states: from mass education programs to fielding modern armies. These administrators needed training. Countries noticed that there was already an institution set up to train people with the skills that administrators and bureaucrats needed. Remember, one of the university’s earliest roles was to train clergy and for a long time the Catholic Church was the biggest bureaucracy in Europe.

Many continental European countries, starting with Prussia and followed closely by France and Italy, began to build new universities and leverage old ones to train the new administrative class. This is really the point where “training the elite” took off as a big part of the university’s portfolio of social roles. Universities and the State became tightly coupled: previously curriculum and doctrine was set by the Church or individual schools — under the new system the state was heavily involved in the internals of universities: in terms of staffing, structure, and purpose.

Technically, not all of these schools were actually “universities.” In the 19th century, universities were only one type of institution of higher education among a whole ecosystem that included polytechnic schools, grandes écoles, and law and other professional schools. Each of these schools operated very differently from the German university model (which, spoiler alert, eventually won out and is what today we would call a university).

With the exception of Prussia, research was a sideshow during the initial shift of universities from largely insulated institutions for training clergy and doing philosophy to cornerstones of the nation-state. Some scientific researchers continued the tradition of using teaching as an income source to sustain their research side-gig, but nobody outside of Prussia saw the role of the university as doing research. From A History of the University in Europe: Volume 3:

Claude Bernard (1813–78) had to make his very important physiological discoveries in a cellar. Louis Pasteur (1822– 95) also carried out most of his experiments on fermentation in two attic rooms.

However, the Prussian system put research front and center for both the humanities and the “arts and sciences” (which is what would become what we call STEM — remember, engineering was considered an “art” until the 20th century). Alexander von Humboldt, the architect of the Prussian university system 3 believed universities should not just be places where established knowledge is transmitted to students, but where new knowledge is created through research. He argued that teaching should be closely linked to research, so students could actively participate in the discovery of new knowledge, rather than passively receiving it.

Prussia’s 1871 defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian war solidified the Prussian higher education system as the one to emulate. Leaders across the world (including France itself!) 4 chalked Prussia’s victory up to their superior education system: Prussian officers were trained to act with far more independence than their French counterparts, which was in part traced back to the Humboldtian research university exposing students to the independent thinking in novel situations that research demands. Superior technology that was downstream of university research was another key component of the Prussian victory — from breech-loading steel cannons enabled by metallurgy research to telegraphs improved by developments in electromagnetism. (From a “where is technology created?” standpoint, these technologies were created at the companies that also manufactured them but built by people who were trained at the new research universities which also advanced scientific understanding of metallurgy well enough that the industrial researchers could apply it.)

Over the next several decades countries and individuals across the world created new institutions explicitly following the German/Humboldtian model (the University of Chicago and Johns Hopkins in the US are prominent examples). Existing institutions from Oxford to MIT shifted towards the German model as well. That trend would continue into the 20th century until today we use the term “university” to mean almost any institution of higher learning.

Over the course of the 19th century, the number of people attending universities drastically increased. In 1840, one in 3375 Europeans attended university and in 1900, one in 1410 did. That is a massive increase in enrollment given population changes, but university degrees were still a rarity and largely unnecessary for many jobs.

Similar dynamics were happening on the other side of the Atlantic — in large part following the European trends.

Before the 19th century, American higher education organizations like Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (which was the College of New Jersey until 1896) were focused on training clergy and liberal arts education for the children of the wealthy. None of these American schools were actually “universities” until they started following the German model and granting doctorates in the late 19th century.

American higher education also took on a role in disseminating new technical knowledge to boost the economy. In the middle of the 19th century, local, state, and federal governments in the US realized that new research in agriculture and manufacturing could boost farming and industrial productivity. Congress passed legislation that created the land grant colleges in 1862. These colleges (note — not universities yet!) included many names you would recognize like Cornell, Purdue, UC Berkeley, and more. These schools were explicitly chartered to use science and technology to aid industry and farming in their areas. Almost simultaneously, technical institutes were springing up (MIT 1861, Worcester Polytechnic Institute 1865, Stevens Institute of Technology, 1861). Both the land grant colleges and technical institutes were originally focused on imparting knowledge rather than creating it, but this would quickly change.

Like their European counterparts, the Americans became enamored with the German research university. Johns Hopkins was the first American university created explicitly in the Humboldtian model. It was founded in 1876 — four years after the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian war. The University of Chicago, founded in 1890, followed suit. During the same period, existing colleges added graduate schools and started doing research — Harvard College created a graduate school in 1872 and the College of New Jersey became Princeton University in 1896.

By the end of the 19th century, universities on both sides of the Atlantic had transformed from an essentially medieval institution to a modern institution we might recognize today:

Institutions with heavy emphasis on research both in the humanities and in the sciences.

Strong coupling between universities and the state — states used the universities both to create and transmit knowledge that improved economic and military capabilities and to train people who would eventually work for the state in bureaucracies or militaries. In exchange, most universities were heavily subsidized by states.

Vocational training was a big part of the university’s role (especially if you look at money flows).

However, there were some notable differences from today:

The role of the university’s research with respect to technology was to figure out underlying principles and train research as inputs to industrial research done by companies and other organizations.

By the end of the 19th century, only one in 1000 people got higher education, so while University students did have a big effect on politics, universities were less central to culture.

While the Humboldtian research university was starting to dominate, there was still an ecosystem of different kinds of schools with different purposes.

A lot of professional schooling happened primarily outside of the university in independent institutions like law schools and medical schools.

While vocational training was a function of the universities, lawyers and there were only a few jobs that required degrees.

Instead of being society’s primary source of science and technology, a big role of university research was in service of education.

This bundle would last until the middle of the 20th century.

20th Century

The 20th century saw massive shifts in the university’s societal roles. A combination of demographic and cultural trends, government policy, and new technologies led to a rapid agglomeration of many of the roles we now associate with the university: as the dominant form of transitioning to adulthood, a credentialing agency, a think tank, a collection of sports teams, a hedge fund, and more. All of this was overlaid on the structures that had evolved in the 19th century and before.

The role of universities in science and technology shifted as well. At the beginning of the 20th century, universities were primarily educational institutions that acted as a resource for other institutions and the economy — a stock of knowledge and a training ground for technical experts; driven first by WWII and the Cold War but then by new technologies and economic conditions in the 70s, universities took on the role of an economic engine that we expect to produce a flow of valuable technologies and most of our science.

The WWII Discontinuity

To a large extent, the role of the university in the first half of the 20th century was a continuation of the 19th century. World War II and the subsequent Cold War changed all of that.

World War II started a flood of money to university research that continues today. This influx of research dollars drastically shifted the role of the university. Many people fail to appreciate the magnitude of these shifts and the second-order consequences they created.

A consensus emerged at the highest level of leadership on both sides of WWII that new science-based technologies would be critical to winning the war. This attitude was a shift from WWI, where technologies developed during the war were used but ultimately had little effect on the outcome. There was no single driving factor for the change — it was some combination of extrapolating what new technologies could have done in WWI, developments during the 1930s, early German technology-driven success (blitzkrieg and submarine warfare), and leaders like Hitler and Churchill nerding out about new technologies.

Like almost every institution in the United States, universities were part of the total war effort. In order to compete on technology, the USA needed to drastically increase its R&D capabilities. Industrial research orgs like Bell or GE labs shifted their focus to the war; several new organizations spun up to build everything from radar to the atomic bomb. Universities had a huge population of technically trained people that the war production system heavily leveraged as the production centers of technology. It didn’t hurt that the leader of the US Office of Scientific Research and Development, Vannevar Bush, was a former MIT professor — while focusing on applied research and technology wasn’t much of a shift for MIT (remember how there were many university niches), it was a big shift for many more traditionally academic institutions.

This surge in government funding didn’t end with the surrenders of Germany and Japan. The Cold War arguably began even before WWII ended; both sides deeply internalized the lessons exemplified by radar and the Manhattan Project that scientific and technological superiority were critical for military strength. The US government acted on this by pouring money into research, both in the exact and inexact sciences. A lot of that money ended up at universities, which went on hiring and building sprees.

Globally, the American university and research system that emerged from WWII became basically the only game in town: because of the level of funding, the number of European scientists who had immigrated, and the fact that so much of the developed world had been bombed into rubble. As the world rebuilt, the American university system was one of our cultural exports. That is why, despite focusing primarily on American universities in the second half of the 20th century, the conclusions hold true for a lot of the world.

Second-order consequences of WWII and the Cold War

The changes in university funding and their relationship with the state during WWII and the Cold War had many second-order consequences on the role of universities that still haven’t sunk into cultural consciousness:

Top universities are not undergraduate educational institutions. If you’re like most people, 5 you think of “universities” as primarily educational institutions; in particular, institutions of undergraduate education that serve as a last educational stop for professionally-destined late-teens-and-early-twenties before going out into the “real world.” This perspective makes sense: undergraduate education is the main touchpoint with universities that most people have (either themselves or through people they know). It’s also wrong in some important ways.

While many universities are indeed primarily educational organizations, the top universities that dominate the conversation about universities are no longer primarily educational institutions.

Before WWII, research funding was just a fraction of university budgets: tuition, philanthropy, and (in rare cases) industry contracts made up the majority of revenue. 6 Today, major research universities get more money from research grants (much of it from the federal government) than any other source: in 2023, MIT received $608 million in direct research funding, $248M from research overhead, and $415M in tuition; Princeton received $406M in government grants and contracts and $154M in tuition and fees.

These huge pots of money for research and the status that comes with it means that the way that higher education institutions become top universities is by increasing the amount of research that they do. Just look at the list of types of institutions of higher education from the Carnegie Classification System and think honestly which of these seem higher status:

Doctoral universities are by far the highest status organizations on the list. Thanks to the Prussians, the thing that distinguishes a doctoral university from other forms of higher education is that it does original research.

The funding and status associated with being a research university exerts a pressure that slowly pushes all forms of higher education to become research universities. That pressure also creates a uniform set of institutional affordances and constraints. It’s like institutional carcinization.

Of course, that Carnegie list also includes many institutions of higher education that are not universities. This fact is worth flagging because it means that when the discourse about the role of universities focuses on undergraduate education, people are making a category error. People often use the Ivy League and other top universities as a stand-in for battles over the state of undergraduate education, but those institutions’ role is not primarily undergraduate education.

Shifts in university research. The paradigm shifts created by WWII and the Cold War also changed how research itself happens.

For the sake of expediency during the war, the government shifted the burden of research contracting and administration from individual labs to centralized offices at universities. This shift did lighten administrative load — it would be absurd for each lab to hire their own grant administrator. However, it also changed the role of the university with respect to researchers: before it was a thin administrative layer across effectively independent operators loosely organized into departments; now the university reaches deep into the affairs of individual labs — from owning patents that labs create to how they pay, hire, and manage graduate students to taking large amounts of grants as overhead.

Federal research funding created multiple goals for university research – both:

To train technical experts who were in some ways seen as the front line of national power in WWII and the Cold War.

To directly produce the research that would enhance national power.

(Recall that in the 19th and early 20th century, the role of university research was much more the former than the latter.)

This role duality has been encoded in law: many research grants for cutting-edge research are also explicitly “training grants” that earmark the majority of funding for graduate students and postdocs.

I won’t dig too deeply into the downstream consequences here, but they include:

A system where much of our cutting-edge science and technology work is done by trainees. (Imagine if companies had interns build their new products.)

Artificially depressing the cost of research labor.

Many labs shifted from being a professor working on their own research and giving advice to a few more-or-less independent graduate students to what is effectively a small or medium-sized business. 7 The role of a professor at a research university looks more like a startup founder crossed with a director in a large organization than anything else.

Strong incentives against increasing lab efficiency — if most of your funding is earmarked for subsidized labor, there is no incentive to automate anything.

As universities took on a central societal role in science and technology, they became a gravity well for managing research. If someone wants to deploy money towards a new research effort or set up a new research organization, the default choice is to house it in or have it be administered by a university. In addition to numerous centers and institutes, universities administer many federal labs and state initiatives: JPL is administered by Caltech, the University of California administers Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Princeton runs New Jersey’s new AI initiative to name a few.

The university’s central role in science and technology has also made it a bottleneck for influencing the culture of research. “Professor” is by far the highest status scientific profession — leaving the university to work at non-university research labs or leave research all together is considered a secondary option. (The words “outcast,” “second-class citizen,” or “failure” are too extreme but there’s definitely an element of it in academic attitudes towards those who have left the university.) In part because almost all researchers were trained in a university and in part because of the status hierarchy, research culture across the ecosystem is downstream of how academia prioritizes things and acts.

Take peer review for example: professors care about it because peer review determines how many grants are awarded and peer reviewed publications are a big component of getting tenure and status more generally. That focus on peer review as the gold standard for research quality then seeps into research culture and beyond.

The university’s central role in research culture means that while there are other kinds of research organizations, like R&D contractors and national labs, academic incentives dominate research far beyond the ivory tower. The dominance of academic incentives was exacerbated by the collapse of corporate R&D and consolidation of independent research labs in the 1980s. Previously places like BBN or Bell Labs acted as equally prestigious career pathways for researchers, with people not infrequently hopping between university and non-university roles. Today that is almost unheard of. Now there is a fairly clear hierarchy of research organization status, with universities and their originally medieval academic roots at the top.

Other 20th Century Roles

There are, of course, many other roles that the university acquired in the 20th century besides research. During the second half of the 20th century, universities quickly accumulated a lot of the bundle that we associate with them today:

The roles associated with being the dominant and status-conferring form of transitioning to adulthood (“Where did you go to college?” is now a standard way of sizing someone up professionally.)

Dating site

Credentialing agency

Dominant thing that 18-22-year-olds do (ie. Adult day care)

The high-status form of job training. (although this trend has reversed slightly.)

Policy leadership through social science research

Sports teams

Hedge funds

Top-tier professional schools

Unpacking those:

Credentialing Agency

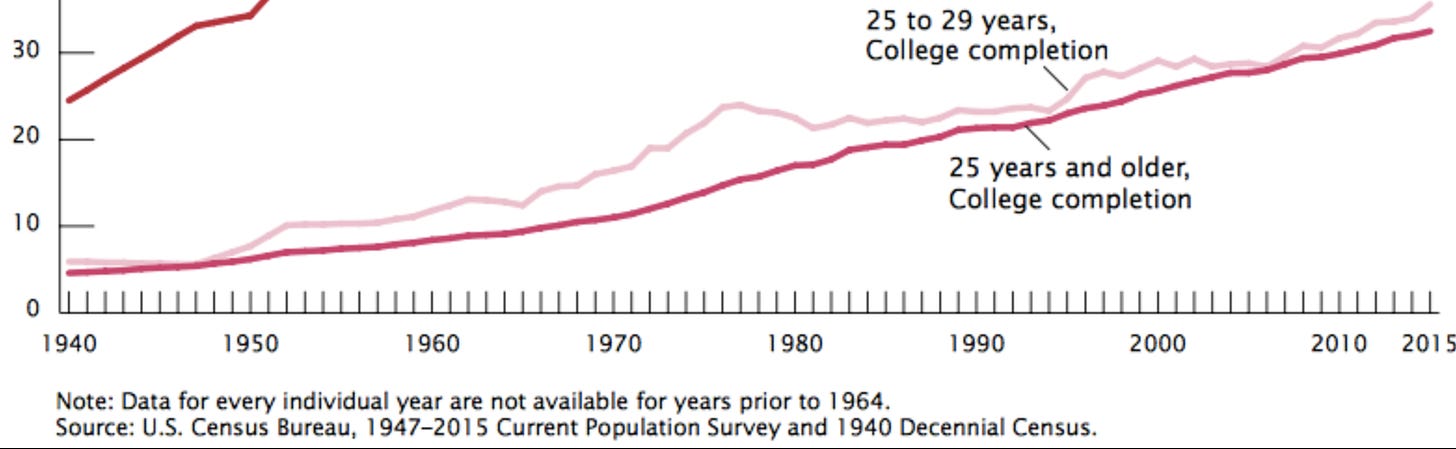

The trend of more and more people getting higher education started in the 19th century, but accelerated in the 20th century. As more people went to college, universities (remember how top colleges became universities) took on the role of a credentialing agency: college and graduate degrees and where they were earned became proxies for someone’s skill and potential job performance.

Degrees have always been a form of credential, but when they were rarer they were not the one credential to rule them all: plenty of people without degrees could perform jobs just as well as people with degrees. As the market became flooded with university graduates, not having a degree became a negative signal. Today, many jobs require degrees, regardless of whether the job actually demands skills you can only pick up in college.

(Slightly spicy) I would argue that contrary to popular conception, as the university’s role as a credentialing agency increased, its role in actually training professional skills has decreased (at the college level). This shift is borne out in the grades data. Instead of A’s indicating exceptional students, they’ve become the most common grade. People practically expect A’s as a participation prize for completing college (especially at elite universities). Grade inflation makes GPAs hold little signal beyond indicating exceptionally bad students; the phenomenon is not dissimilar from college attendance itself.

From National Trends in Grade Inflation, American Colleges and Universities

(As with college attendance, attitudes towards degrees may be shifting but as of early 2025, universities still maintain a firm grip on their role as credentialing agencies.)

High-status form of transitioning to adulthood

Over the 20th century, going to college at an elite university became the high-status way to transition to adulthood. Higher education shifted from something for the wealthy and people who were training for specific professions to a thing that all people aspiring to be upper middle-class professionals did.

Today, where you went to college is a status signal; many educated professionals will look askance if you didn’t go. (This attitude is changing among some subcultures, so perhaps the curve has inverted, but the vast majority still think of college as the thing you do if you want to be successful.) Universities have taken on the societal role of shepherding people into adulthood and bestowing status as they do so.

The role as high-status-adulthood-transition-path came bundled with a number of other roles:

The default way for people to figure out what to do with their lives.

A dating market (people want to marry people of similar or higher status).

A country club for 18-22 year olds. (Many colleges compete on “student experience.”)

Think Tank

Since WWII, the “inexact sciences” have flourished — fields like sociology, political science, and economics (which was quite older). The research from these fields is naturally more directly applicable to government policy than the humanities or “exact sciences”: asking everything from “what is the effect of minimum wage?” to “what interventions increase voter turnout?” As a result, universities became more central to political conversations, with some departments acting similarly to think tanks.

Universities have been a policy apparatus of the nation state since the 19th century -- as a way of increasing economic productivity, training bureaucrats, and promulgating official doctrine — but the rise of the social sciences turned the university from a policy output into a policy input .

From https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2006/08/21/rise-social-sciences which in turn got it from https://www.amazon.com/Reconstructing-University-Worldwide-Academia-Century/dp/0804753768. These numbers are for the British commonwealth because of data availability but the authors explicitly say that the US followed very similar trends.

Collection of sports teams

College sports morphed from an activity just for students and university communities to a massive entertainment business. College sports are now a billion dollar business; most of that growth happened after WWII. Some college football coaches are paid more than the president of their university.

Hedge Fund

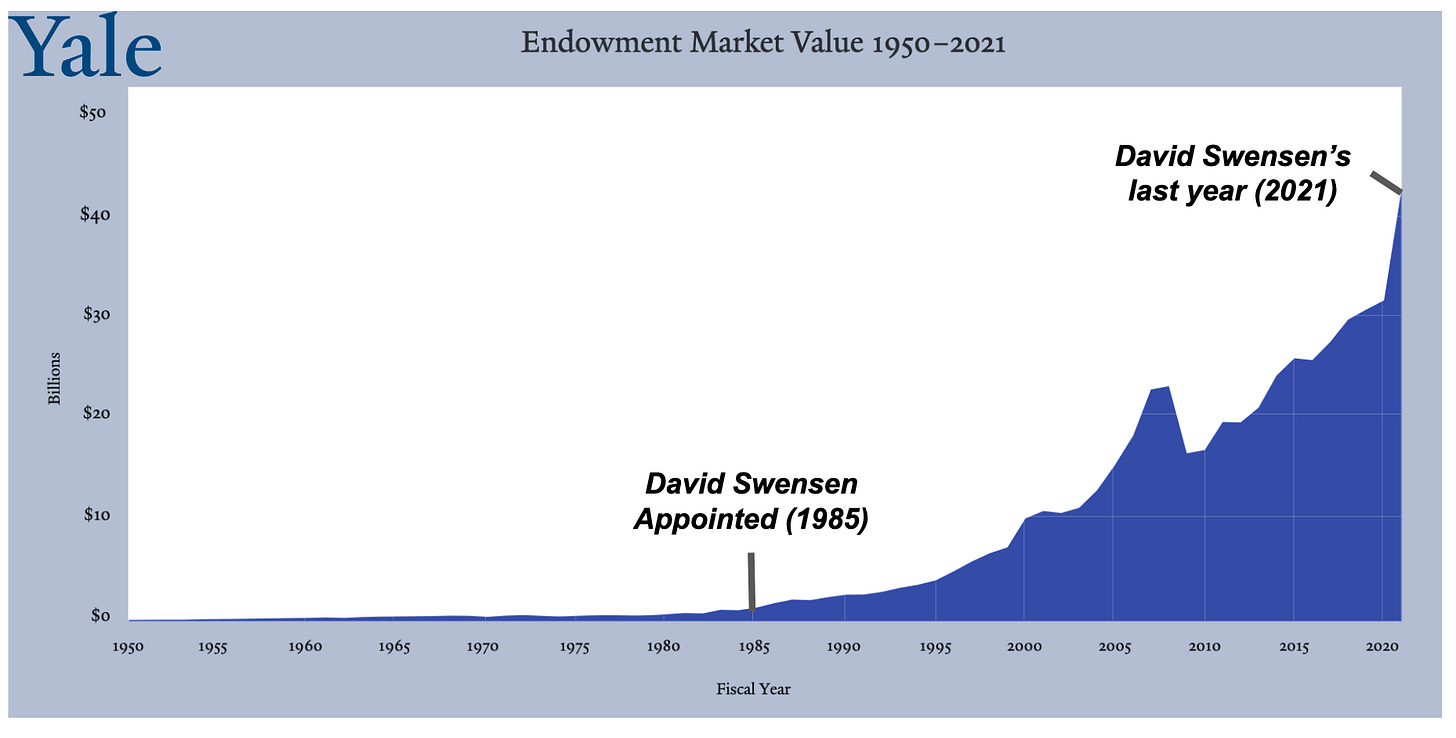

University endowments grew enormously in the second half of the 20th century through a combination of favorable market conditions, professionalization, and active investment. 20% of Stanford’s $8.9B revenue in 2023 came from their endowment (topped only by the revenue from health services). The largest endowments now control tens of billions of dollars and grow significantly faster than the universities can spend them.

As a result, many universities have become financial institutions that can have significant effects based on what they do or do not invest in.

Source https://www.moneylemma.com/p/lessons-from-the-yale-endowment

A home for top-tier professional schools

Professional schools and universities became more intertwined over the course of the 20th century. In the 19th century, many top-tier medical and legal schools were independent organizations. Over the 20th century, accreditation, standardization, and the integration of research into professional curricula pushed professional schools towards university affiliations. There are certainly still independent professional schools — nursing, art, etc — but if you think of most top-tier professional schools, they are integrated with a university.

This shift is notable because these professional schools bring in huge amounts of revenue to universities — 23% of Stanford’s income comes from Health Care services associated with its hospital and medical school; University of Michigan’s Medical activities provide 55.1% of their total operating budge.; In 2013, the university’s medical center contributed 45% of the overall university budget of $2.6 billion. Like major revenue sources for any businesses, these professional schools warp institutional attention and incentives around themselves.

The consolidation of all these roles into a single institution was amplified by a collapse in the types of higher education institutions, especially in the United States. At the beginning of the 20th century, a polytechnic institute was a very different thing from an agricultural school and both were very different from a proper liberal arts university. By the end of the century, the distinction is primarily between undergraduate-only institutions and universities that have both colleges and graduate schools.

Post 1980 pre-commercial technology research and bureaucracy

The economic conditions of the 1970s created a major shift in the role of the university around technology creation.

If you ask most people “how does technology happen?” the near-ubiquitous answer will gesture at some form of “people do basic research in a university and then commercialize it by spinning it out into a startup or licensing it to a big company.” That is a surprisingly contemporary view.

The role of universities in economically valuable technology shifted in the 1970s from primarily being a resource for other institutions — a stock of knowledge and a training ground for technical experts — to an economic engine that produced a flow of valuable technologies.

This story from Creating the Market University illustrates the shift wonderfully:

On 4 October 1961, the president of the University of Illinois received a letter from Illinois governor Otto Kerner. In the letter, Governor Kerner asked the flagship institution to study the impact of universities on economic growth, with an eye toward “ensuring that Illinois secures a favorable percentage of the highly desirable growth industries that will lead the economy of the future.”

In response, the university convened a committee that met for the next eighteen months to discuss the subject. But despite the university’s top-ten departments in industrially relevant fields like chemistry, physics, and various kinds of engineering, the committee was somewhat baffled by its mission.? How, it asked, could the university contribute to economic growth? Illinois faculty could act as consultants to companies, as they had done for decades. The university could provide additional training for industrial scientists and engineers. Scholars could undertake research on the economy. But, the committee’s final report insisted, “certain basic factors are far more import- ant in attracting industry and in plant location decisions, and therefore in stimulating regional economic growth, than the advantages offered by universities.”? In 1963, the University of Illinois —like almost every university in the United States—-had no way of thinking systematically about its role in the economy.

In 1999, thirty-six years later, the university faced a similar request. The Illinois Board of Higher Education declared that its number-one goal was to “help Illinois business and industry sustain strong economic growth.” This time, though, the university knew how to respond. It quickly created a Vice President for Economic Development and Corporate Relations and a Board of Trustees Committee on Economic Development.- It titled its annual State of the University report “The University of Illinois: Engine of Economic Development.” It expanded its program for patenting and licensing faculty inventions, launched Illinois VENTURES to provide services to startup companies based on university technologies, and substantially enlarged its research parks in Chicago and Urbana-Champaign. It planned to pour tens of millions of dollars into a Post-Genomics Institute and tens more into the National Center for Supercomputing Applications.

Before the late 1970s, technology was primarily created by individuals and companies and then studied and improved by university labs. An airplane company would create a new wing design and then bring it to a university to analyze it with their wind tunnel or a radio company would ask a university lab to understand how their antenna design affected signal propagation. After the 1970s, universities took on the societal role as a source of innovation and an economic engine fueled by commercializing those innovations. That is, people started looking to universities as the starting point for useful technologies.

Four coupled factors drove this role shift:

New technologies that easily went straight from academic lab to product — particularly biology-based technologies like recombinant DNA that was behind the success of companies like Genentech.

The rise of venture capital that could fund those spinouts.

Dire economic conditions and the sense that America had lost its innovation mojo which had politicians asking “how do we create more innovation?”

Pressure on companies from shareholders and elsewhere caused them to scale back internal R&D work that wasn’t focused directly on existing product lines.

(Quick aside on the term “innovation.” “Innovation” is a fuzzy, ill-defined, overused word but generally has the implication of both novelty and impact. Interestingly, it only became a “thing” in the time period we’re talking about – the 1970s. My unsubstantiated hypothesis is that as friction to getting things out into the world increased, it was no longer sufficient to just invent something, you also needed to do a lot of work on diffusion in order to turn that invention into an innovation.)

To drastically compress a story that the book Creating the Market University gives the full treatment it deserves: the US economy was in the dumps in the 1970s and politicians were desperate to find a solution. One class of solution was to make it easier to fund and start small technology companies. The 1979 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) allowed pension funds to invest in VC firms, which drastically increased the amount of money available to invest in startups: new money to VC firms rose by an order of magnitude from $218M in 1978 to $3.6B in 1983. The Bayh-Dole Act gave universities clear ownership over IP derived from government funded research, with the idea that it would make it easier for university research to become VC-funded startups.

These interventions happened at the same time as the creation of recombinant DNA at Stanford, which kicked off the entire biotech industry. This success created today’s cultural template that technology happens by academic lab work spinning out into high-growth startups that go on to change the world, despite the fact that health-focused biotechnology is amenable to academic lab work spinning off into successful companies for reasons that often don’t apply to other technologies.

Legislation encouraging university spinouts and technologies that were especially amenable to being spun out into VC-funded startups coincided with companies scaling back exploratory R&D in corporate research labs. Driven in part by shareholder pressure towards efficiency, companies shifted towards acquiring derisked technology through licensing, working with startups, or buying them. (This explanation of the decline of corporate labs is a gross oversimplification, of course. See The Changing Structure of American Innovation for far more thoroughness or my notes on it here. )

All of these factors combined to effectively give academia a societal monopoly on pre-commercial technology research.

Final role: a massive bureaucracy

As universities acquired more and more societal roles, they have both come under more scrutiny and more administrative demands imposed by fulfilling all those roles under one roof. As a result, university bureaucracies have exploded in size.

Part of the administrative growth is simply due to requirements imposed by the university’s roles: federal grants have near-book-length compliance requirements, managing buildings being used for everything from chemistry labs to sporting events to dining halls requires a small army, and college rankings take into account how high-touch an experience students get.

Partially, the bureaucracy is downstream of the forces also reshaping the rest of the world: the internet, rising standards of living, and drastically increased litigiousness.

The internet has flattened the world, making it much easier for people to realize that college is an option, what the best colleges are, and to apply to them. This is wonderful! But it also means that there is drastically more competition to get into colleges, higher expectations on the college experience, and a wider range of preparation going into college and ideas of what the college “product” is; handling all of this demands more administrators.

Rising standards of living are also a good thing! They also have turned education at top universities into a highly-sought-after luxury good. The way that universities compete is to have more and more “perks,” all of which come with more administrative overhead.

Increased litigiousness means that universities have implemented many more bureaucratic procedures to cover their butts and avoid lawsuits. (And their many roles have increased the number of things they can be sued for.) These bureaucratic procedures need bureaucrats to enforce them.

Conclusion

So there you have it: a speed run of the university’s transformation from a priest training center that did philosophy on the side to a credential-and-status-granting-rite-of-passage-hedge-fund-sports-team-think-tank-source-of-all-science-and-technology.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

As you mention "Teach well enough to get paid" is the secret mantra of many professors in academia today. Most of my coworkers treat teaching as an annoying secondary to their research work. It's not that they're nefarious people but the system is structured that way. You need to: develop a research program, mentor graduate students, chase grants, disseminate work at conferences, have some role administrating a department... and by the way teach possibly 100s of students in topics they don't necessarily enjoy. It feels like a challenging situation for all involved. Thanks for the work bringing attention to the history of how we got here!

Very interesting overview of the history of the university.