The Value of Stability in Scientific Funding, and Why We Need Better Data

A fascinating paper was just released online: “Scientific Talent Leaks Out of Funding Gaps,” by Wei Yang Tham, Joseph Staudt, Elisabeth Ruth Perlman, and Stephanie D. Cheng. As far as I know, it’s the first paper taking a detailed look at the employment outcomes for scientific personnel (often graduate students or post-docs) who were employed by an NIH grant that was delayed by 30 days or more in being renewed.

This question may sound like it’s fairly arcane, but it’s not.

A given scientist’s funding can fluctuate dramatically up and down (causing funding gaps), and that’s a huge issue for how scientists spend their time, hire people, and structure their research agenda over time.

It’s hard to do good science when you’re flush with money one year, but worried about running out of money the next, or when you’re worried that congressional delays in adopting a budget will end up delaying the processing of NIH grants.

As one prominent researcher at a top-5 university told me:

If I need several post-docs to run my lab, and I have a 20% chance of getting funded, I have to apply for a ton of grants. In one prior year, I applied for 10 R01s, and not a single one got funded. I spent virtually all my time on grant proposals that year, and the mental toll was difficult to take. That said, the next year, I got 3 of them funded in a row as resubmissions.

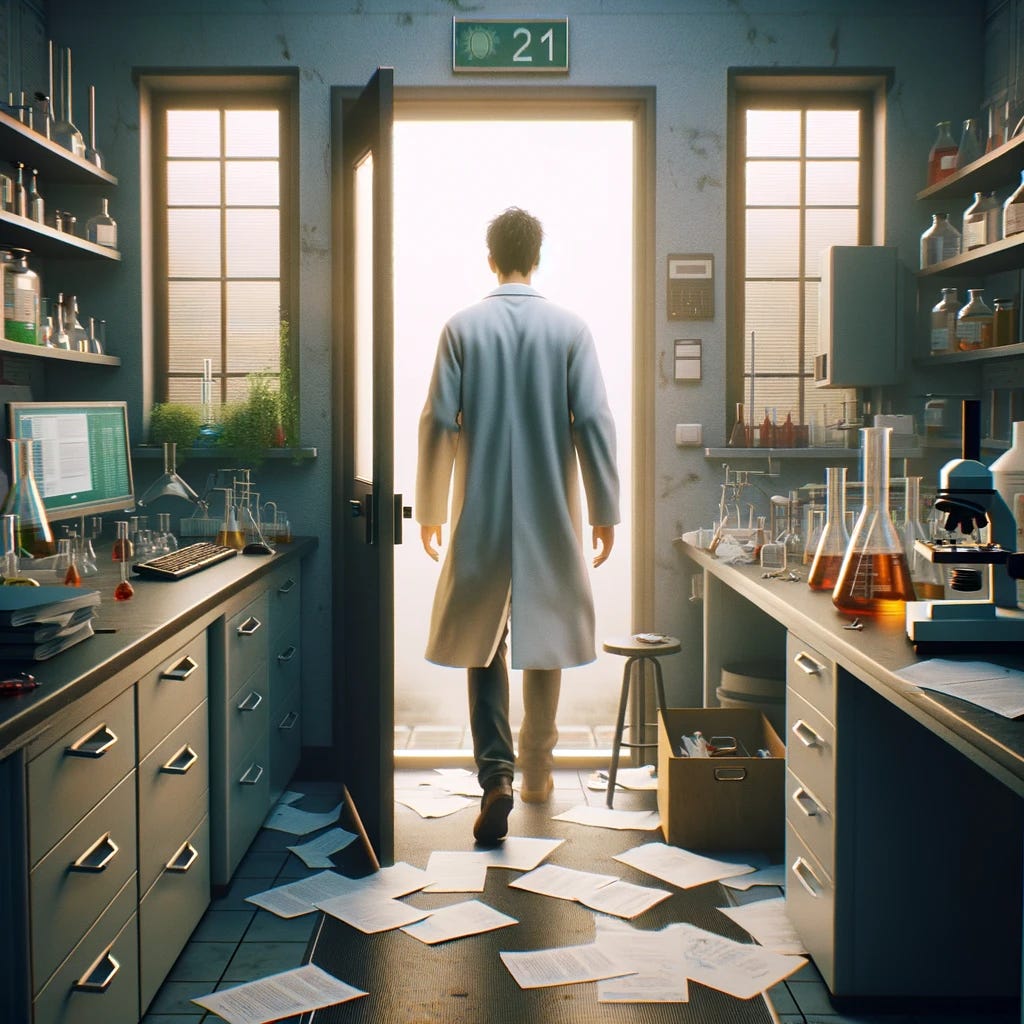

This “feast or famine” nature of research funding makes it hard to maintain a research program. We need more stability and predictability in our funding stream.

In other words, if a scientist gets a grant from NIH at one point, but later has a delay in the renewal process, he or she may well have to worry that a post-doc hired under the earlier grant will have to be laid off. It’s hard to plan for those kinds of delays, especially given that, unlike startups or businesses, scientists generally don’t have customers and can’t take on debt. They are at the mercy of funding agency timelines that may be delayed by the peer review process, by congressional inaction, or a number of other factors.

OK, so what about the new paper?

The objective was to see what happens to personnel who are employed by a principal investigator with one NIH R01 grant that gets renewed. Of note here: Over the 2005-18 time period, more than 20% of the successful renewals had a funding gap of over 30 days. So the researchers were able to compare a set of grants that were all fairly alike except for having a funding gap.

The key finding: “After an interruption, personnel in labs supported by a single R01 are immediately 3 percentage points (pp) more likely to become nonemployed in the US (i.e., they do not appear in our comprehensive tax and earnings data), an almost 40% increase.”

For further detail, the paper adds: “These employment effects are concentrated among trainees (graduate students and postdocs) and the US-born, who are 6.1 pp and 3.5 pp more likely to enter US nonemployment, a 60% increase for both subsamples. For both groups, these changes are almost entirely driven by departures from universities.”

Maybe some people leave universities only to get higher-paying jobs in industry? Nope: the paper finds that “after an interruption, the relative earnings of single-R01 personnel decline by 20%.”

By the way, the “interrupted and continuously-funded labs are similar across a variety of pre-treatment observables, including demographic characteristics (gender, race, ethnicity, and place of birth), occupational composition, and research production.”

Also worth noting: These results are ONLY for researchers with one, and only one, NIH grant. If a lab has more than one NIH grant at a time, there were “zero post-interruption changes for all employment outcomes.” Such labs are apparently far better able to handle the temporary loss of funds from one grant by shifting money around from other grants (money is fungible, after all).

In short, when someone has one NIH R01 grant and there’s a 30+ day gap between the original grant and the renewal, that raises the chance that graduate students and postdocs are no longer employed in the future—not by the university, and not anywhere else—and that their earnings may be lower on average.

How do the researchers track whether these folks are employed anywhere and what their earnings are?

Here’s what is so cool about the study: the researchers were able to draw on a rich set of data sources that include not just NIH and university data, but IRS and Census data that include all tax returns and employment information in the United States.

For our analysis, we need three key pieces of information: (1) which R01 grants were expiring but eventually successfully renewed, (2) which personnel were part of labs that depended on those R01s, and (3) the labor market outcomes of those personnel.

We obtain these data from:

(1) ExPORTER – a public database of NIH grants,

(2) UMETRICS – administrative grant transaction data from universities (including payments to personnel) [PS: this dataset includes 33 universities that received about 1/3rd of federal research money, so it could be expanded], and

(3) IRS/Census data including the universe of W-2 and 1040 Schedule C (1040-C) tax records and the universe of unemployment insurance (UI) earnings records.

Together, these data allow us to identify personnel working in labs with a successfully renewed R01 (but potentially experiencing a funding interruption) and track their entire US employment and earnings history.

Conclusion

There are two takeaways from this study:

We likely need some mechanism to smooth out NIH funding from year to year, so that scientists don’t face dramatic swings or gaps in funding over time. When funding is unstable and unpredictable for each individual scientist and his/her lab, that forces scientists to spend way too much time submitting extra proposals. And as this paper shows, it also forces some people out of biomedicine or even employment not due to merit but to funding timelines.

As an initial matter, perhaps NIH should explore extending bridge funding to single-R01 investigators for up to 6 months after a grant’s expiration; this could be taken out of the renewal grant (if any). Further, NIH could explore mechanisms to smooth out funding for multiple-R01 labs, so that yearly fluctuations aren’t as anxiety-inducing.

At a broader level: Too many studies about science policy and funding depend on outcome measures like citations or patents. We need many more studies that draw on rich, detailed, longitudinal data as to the longer-term paths of scientists’ employment.

Full disclosure: The Social Science Research Council (to which I’m a senior advisor) has a major grant from NSF to pilot this kind of data work as to NSF investments, but the effort needs to be expanded 10x or 100x. Agencies and/or Congress should fund databases like UMETRICS to partner with more state governments that have full access to unemployment and earnings data. It will be labor-intensive, but the resulting database will then be accessible to science funding agencies, state governments, and any interested researcher who wants to use it.

Such data efforts would let us get a far better read on the overall impact of science funding from NIH, NSF, etc., the impact of specific funding policies and initiatives, and many state-level questions (such as the nature of the innovation clusters in a state, and who is being hired by firms in those clusters, and how they were trained).