Governmental Efficiency: What Can It Possibly Mean?

In theory, the Good Science Project endorses the proposed Department of Governmental Efficiency that Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy have been promoting now that Trump got elected. After all, we have published numerous articles about how scientists are affected by administrative burden (44% of their research time in surveys, although it can be up to 70% of their time in anecdotal cases that I’ve heard about!).

That said, what little we know about DOGE so far suggests that there are a number of distractions or even counterproductive ideas, mixed in with some good ideas. The impact of this initiative could be enormous—if focused on actually reducing bureaucratic burdens, not on firing employees or defunding science.

Does Efficiency Mean Firing Government Employees?

On a recent podcast, Vivek said this:

"Day 1, anybody in the federal bureaucracy who's not elected, whose Social Security number ends in an odd number, you're out. [Day 2], of those who remain, if your Social Security starts in an even number, you're in, and if it starts with an odd number, you're out. That's a 75% reduction."

"Now imagine that you could run that thought experiment at scale, but you had a metric for screening people who had the greatest competence, as well as the greatest commitment and knowledge of the Constitution. That would immediately raise not only the civic character of the United States... it would also stimulate the economy. The regulatory state is like a wet blanket on the economy."

"One of the virtues of that thought experiment is you don't have a bunch of lawsuits you're dealing with about gender discrimination or racial discrimination... [And] the reality is... on Day 3, not a thing will have changed for the ordinary American, other than their government being a lot smaller and more restrained, and spending a lot less money."

This isn’t a very good idea, apart from whether Social Security numbers are random (they’re not! Vivek’s idea would target people born on the eastern/southern sides of the country).

First, firing even half of government employees wouldn’t save that much money in the grand scheme of things.

How much do we pay government employees ? According to the Congressional Budget Office:

The federal government employs about 2.3 million civilian workers—or 1.4 percent of the U.S. workforce—in jobs that represent over 650 occupations at more than 100 agencies. It competes with private-sector employers for people who possess the mix of attributes needed to do the work of its various agencies.

In fiscal year 2022, the federal government spent roughly $271 billion to compensate those civilian employees. About 60 percent of that total was spent on civilian personnel working in the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Department of Homeland Security.

In 2022, the federal deficit was $1.4 trillion. So if you fired half of civilian employees (which would be monumentally difficult), that would save less than 10% of the deficit, leaving another 90+% of the deficit untouched.

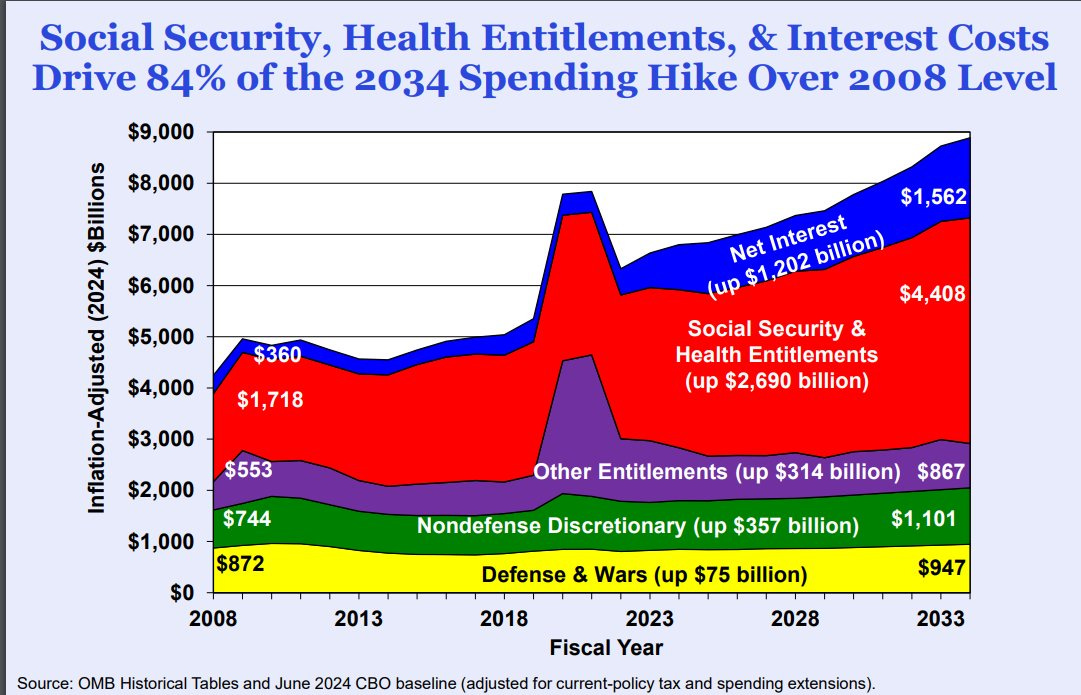

There’s no way to meaningfully reduce the deficit without cutting Social Security, Medicare, Defense, and Medicaid. Government employees are a sideshow compared to the big-spending programs.

Consider this chart from Brian Riedl:

Second, let’s say that by some miracle someone did fire half of all government employees. That would mean decimating the Departments of Defense, Veterans Affairs, and Homeland Security. Almost all of those people are not even part of the “regulatory state”!

If you fire Border Patrol agents, air traffic controllers, transportation workers, or line employees at IRS, you’re not reducing the regulatory state, you’re making it harder to control the border, fly anywhere, repair a collapsed bridge, or answer the phones at IRS (it’s already hard enough to get help).

As economics professor Jason Abaluck has pointed out, if we fired a bunch of DMV workers, that wouldn’t make anyone’s life better. People still need to renew their drivers’ license or vehicle registration, and if each employee now has to handle the work of 2 or 3 people, we’ll all be stuck in line forever.

That is the opposite of efficiency.

To be clear: I’m sure that there are many federal agencies with an inefficiently high number of employees or levels of management. It might even make sense to have a 10% reduction in head count for many agencies, and then see how that works out. But firing half or 3/4ths of people willy-nilly is not a good path to efficiency unless you’re also addressing the many substantive issues that Congress has asked an agency to address (whether regulation or service provision).

That’s a lot harder, because substantive issues mostly require congressional approval, and a thoughtful restructuring would require knowledge about what the agency actually does.*

* Discourse about the Department of Education doesn’t bode well in that regard!

What About Addressing Wasteful Spending?

Is there waste, fraud, and abuse in federal spending?

Sure.

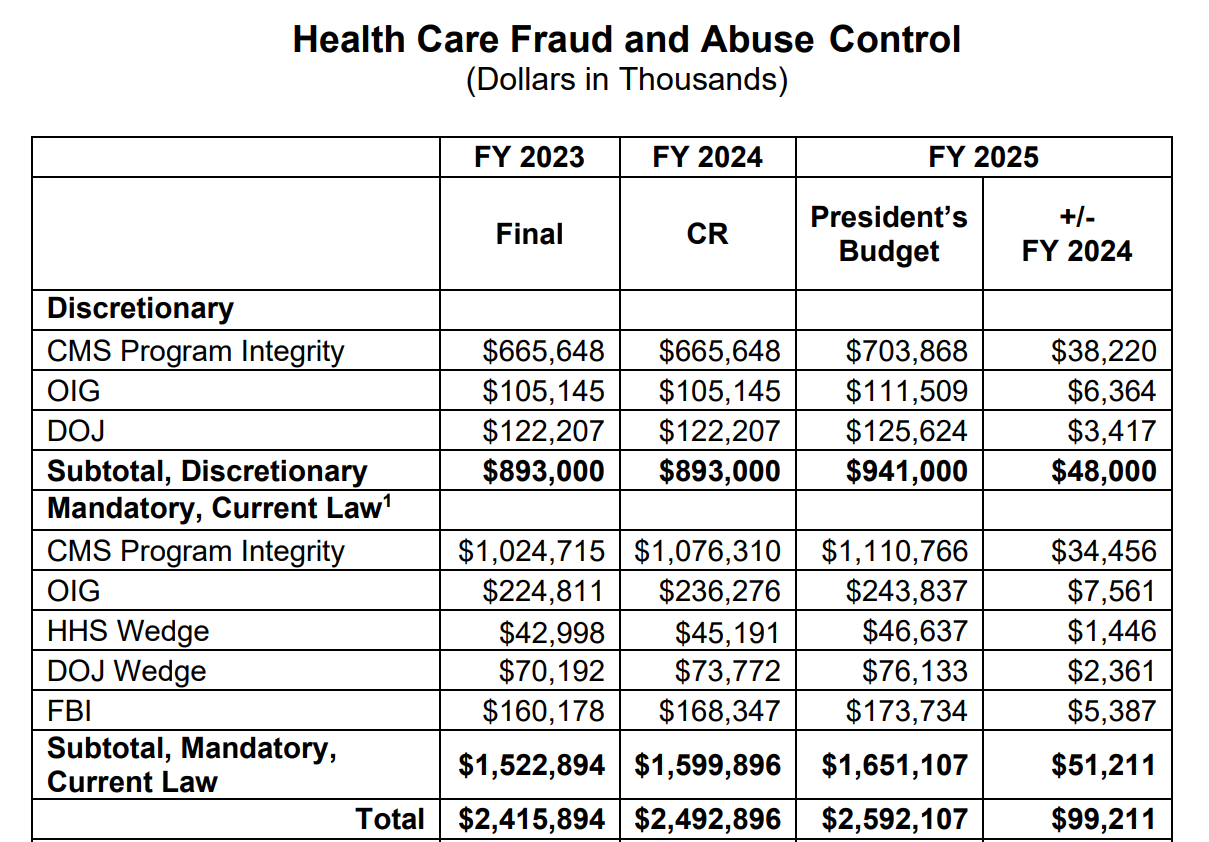

In fact, there’s already an entire government agency (GAO) that investigates waste/fraud/abuse (I hope 3/4ths of them don’t get fired at random!), and we already spend some $2.5 billion a year just trying to find fraud, waste, and abuse in Medicare and Medicaid:

Now, Elon has retweeted a recent GAO report finding that despite any anti-fraud efforts to date, there are 18 federal agencies that made an estimated $247 billion in “improper payments” in 2022.

That sounds like a lot!

But what do we actually do about it? It might help to know why the payments were improper. The GAO report tells us that by far, the most common reason behind a payment being “improper” was “insufficient documentation.”

Hmmmm.

Lack of documentation could mean fraud or negligence. But in many cases, it just means that there are too many hoops to jump through, and the user interfaces are terribly designed, and the technology doesn’t work very well, such that some people or organizations don’t manage to come up with the right documentation.

Consider the fact that the highest rate of “improper payment” (47.5%!) was seen for “long term services and supports” provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs. What does that mean? Things like home healthcare to keep people out of nursing homes, nursing homes themselves, palliative and hospice care for people who are dying, etc.

Indeed, GAO’s Table 2 says that as of 2017, literally 100% of VA’s payments for long-term support were improper!

Wait, what?

Are we to believe that in 2017, zero veterans in all of America needed nursing home support, hospice care, etc.? Absurd. Thus, whatever the GAO was tracking here has to be largely a matter of inane paperwork, not fraud or abuse.

Imagine that a Vietnam War veteran with Alzheimer’s doesn’t produce all of the necessary documentation to pay for his care at a nursing home. Technically, an “improper payment.”

Do we want to toss him out on the street? I’d suggest not.

Whoever addresses these problems needs to think carefully about the balance between false positives and false negatives. To be blunt, how many elderly veterans do you want to put on the street to have a zero percent “improper payment” rate?

As for solutions: We could develop technological tools and software to streamline things like identification, matching with other databases (whether death databases or income databases), collecting application information, and just simplifying any number of processes where it’s easy to make a mistake.

At the same time, if DOGE isn’t careful, any efforts here could well lead to more bureaucracy and inefficiency than ever!

Back in 2010, there was a major scandal: a government conference held in Las Vegas featured a clown and a mind reader.

There are now a bunch of detailed rules and regulations about when, where, and how government employees can travel anywhere, what conferences they can put on and what can happen at such conferences, and so forth.

Is it optimal for a government conference to be held in Las Vegas and to feature a clown, etc.? No . . . although there are many worse things that could have happened in Las Vegas!

But is it efficient to try to prevent any and all frivolous expenditures from ever occurring? Probably not!

What’s more efficient: Occasionally paying for a clown conference, or making 2 million government employees each spend 5 hours jumping through hoops every time they need to attend/host a conference?

As Patrick McKenzie says, the optimal rate of fraud is non-zero. Efforts to minimize fraud, waste, and abuse can create far more paperwork and bureaucracy than they are worth.

Bottom line: DOGE should focus on fraud/waste/abuse only if it is able to balance the tradeoffs at hand, and if it can find solutions that don’t just create more bureaucracy than ever. Indeed, one of the main sources of bureaucracy and inefficiency is the fact that people want to crack down on every example of fraud, waste, and abuse.

What About Canceling Unauthorized Programs and Agencies?

Vivek tweeted recently:

We shouldn’t let the government spend money on programs that have expired. Yet that’s exactly what happens today: half a *trillion* dollars of taxpayer funds ($516 B+) goes each year to programs which Congress has allowed to expire. There are 1,200+ programs that are no longer authorized but still receive appropriations. This is totally nuts. We can & should save hundreds of billions each year by defunding government programs that Congress no longer authorizes. We’ll challenge any politician who disagrees to defend the other side.

Basically every politician will defend the other side here. It’s important to know that appropriations automatically mean some level of authorization, as well as what the “unauthorized programs” even are (the biggest item here is veterans’ health care!). Indeed, Congress can appropriate money for decades to agencies that have never technically been “authorized” in the first place (which is the case as to CDC).

Vivek and Elon seem to think that if a government program/agency isn’t technically “authorized” at the moment, then any spending is “unauthorized” in the colloquial sense—as if there is some treachery, cheating, or skullduggery involved. That is simply wrong.

What About Wasteful Scientific Studies?

DOGE folks have been positively retweeting stuff like this New York Post story:

. . .

In 2021, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) awarded $549,000 to a Russian lab performing experiments on cats, including removing part of their brains and seeing if they could still walk on treadmills, according to the Washington Times.

. . .

Spending by the NIH includes $33 million to a firm that runs “Monkey Island,” a colony of around 3,000 primates sent to research labs. Additionally, NIH grants totaling $3.7 million funded a study on monkeys and gambling. Part of another $12 million went to the University of Mississippi to test monkeys on methamphetamine, and a Florida lab received $477,000 to help fund research into “transgender” monkeys — males injected with female hormones.

First, whenever someone describes a scientific study in simplistic terms, there’s probably a deeper rationale behind the study. (Maybe not, but it’s worth looking.) Turns out that the cat-treadmill study is actually about “spinal cord injuries and body motion.”

We can’t deliberately cause spinal cord injuries in human beings in order to see the results (and maybe someday figure out how to cure them), so we have to do it to animals. Whatever you think of the ethics here, the rationale isn’t ridiculous. How else would you study spinal cord injuries?

As for the “transgender monkey” study, the actual study was trying to investigate why transgender women are so susceptible to HIV, and whether “feminizing hormone therapy” (FHT) might play a role. So, the study aimed to look at these questions:

1) Does FHT increase the availability of HIV-susceptible CD4+ T-cells in vivo? To answer this question, we will use flow cytometry to assess the frequency and phenotype of memory CD4+ Teens in blood and gut biopsies from male rhesus macaques receiving FHT (Group 1) or placebo (Group 2). By comparing the levels of activated CD4+ T-cells between animals in Groups 1 and 2, this analysis will reveal whether FHT modulates a crucial marker of HIV susceptibility in biological males.

2) Does FHT interfere with adeno-associated virus (AAV}-vectored immunoprophylaxis?

Again, this isn’t as comical as the headline would have you believe.

But I don’t want to get into the merits of every individual study, because that’s a distraction.

Even if all of the studies mentioned to date are actually ridiculous, I don’t care and neither should you.

Many of the greatest discoveries in biomedical history have come from experiments that seemed ridiculous at the time, whether it’s Peyton Rous’ experiments on transplanting tumors from one chicken to another (which won him a Nobel 50+ years later, was the first discovery of an oncovirus, and led to future work on retroviruses like HIV), or Thomas Brock’s vacation in Yellowstone Park that ended up discovering a key component to PCR, or research on Gila monster venom that led to amazing diabetes drugs (see this article for even more examples).

Biology is full of mysteries, and for all of our progress, we have barely scratched the surface. If the past is any guide, the greatest breakthroughs 20, 30, 40, 50 years from now will be traced back to experiments that nearly everyone today (even other scientists!) would describe as frivolous.

It is impossible to maximize future breakthroughs by micromanaging scientists today based on what we already know will have impact. Thus, even if the federal government does fund some frivolous studies in biology and medicine, that’s great! It’s one of the main ways to increase future breakthroughs—-like a venture capitalist, we should fund a bunch of ideas that are outside the box and might fail, but one of them will end up curing a type of cancer.

What’s the Path Forward?

Stop complaining about isolated scientific studies that have a trivial budget and that could lead to future breakthroughs.

Stop complaining about the number of government employees or the number of government agencies.

However tempting, these issues are small expenditures in the grand scheme of things, and trying to “fix” them could be counterproductive by slowing down government more than ever.

As well, “waste, fraud, and abuse” aren’t simple to solve. Remember the tradeoffs involved, and aim for streamlined technology solutions that will solve what is often the root cause (“insufficient documentation”).

Finally, stop promising major reductions in debt (unless you somehow come up with the political will to tackle Social Security, Medicare, etc.).

But there are many opportunities to make a huge difference

My colleagues at the Foundation for American Innovation and the Institute for Progress have already put together some ideas. To reiterate and build upon that:

First, focus on issues where the federal government has imposed laws/rules/regulations that hold everyone else back—such as NEPA, overbearing environmental regulations, the Paperwork Reduction Act, and so forth. Then figure out how best to reduce those burdens—legislation, executive order, agency regulations, etc. The impact will be far greater than anything you could accomplish just by cutting government staff.

Second, pick some cases where you can set ambitious goals, while letting the agency experts figure out what is needed—akin to what Elon has done in his private companies such as Tesla and SpaceX.

For example, go to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, and tell them to do whatever it takes to get an 80% reduction in the timeline for getting reactors approved while retaining only what is actually necessary to ensure safety.

Maybe they’ll come back and say they need to cut a layer of middle management, but maybe they’ll say that they need to hire extra staff to meet requirements X, Y, and Z in time, or maybe it just isn’t possible unless a particular statute is reformed. Whatever they say, you now have a path forward to streamline nuclear approvals.

For another example, scientists say in national surveys that they spend over 40% of their research time on paperwork and bureaucracy. No one thinks this makes sense, but any one administrative requirement (such as tracking time/effort) is hard to cut. Thus, how about issuing a mandate to all executive branch agencies that spend more than $100 million a year on R&D: Reduce the burden on scientists’ time to 20% within the next 3 years or else face a budget cut equal to the percent of time that scientists are spending on bureaucracy (e.g., 30%).

Maybe that’s not even possible, and a stark budget cut (if implemented) wouldn’t help scientists either . . . but as Samuel Johnson famously said, “Depend upon it, sir, when a man knows he is to be hanged in a fortnight, it concentrates his mind wonderfully.”

It’s often better to set ambitious goals and let the agency experts figure out how to meet them, as opposed to wading into complicated issues and demanding a particular solution like “cut your budget” or “cut your staff” or “stop doing this particular thing [even if it turns out to be very important].”

Third, take on the problem of outdated IT systems (Elon recently tweeted about this problem). Figure out how to cut through typical procurement regulations so as to get a handful of 10x engineers to fix the problem in 3 months rather than spending $100m+ (and many years) for a Deloitte to deliver a product that doesn’t work (see here and here). Procurement regulations aren’t that sexy. But they’re important. [PS: Please read Jen Pahlka’s Recoding America!]

Fourth, as Tyler Cowen suggests, develop a plan to make it far easier to conduct clinical trials in medicine:

There are regulations concerning hospital protocols, the design of the trials, FDA requirements, the procedures of universities and institutional review boards, and the handling of data, among other barriers. America can have better and speedier approval procedures without lowering its standards.

Of all the tasks I’ve outlined, this is by far the most difficult, because it involves changes in so many different kinds of institutions. Yet it has one of the highest possible payoffs, because more treatments might be developed and made available if the clinical trial process weren’t so onerous.

Fourth, reforming government is hard. Look for low-hanging fruit, such as the many cases in which government employees are trying to do the right thing but are held back by overly risk-averse lawyers.

***

In short, figure out what has the highest burden on the overall economy or on government activities; set ambitious targets; and then help people meet those targets with whatever is necessary (legislation, executive orders, or even extra staff). The impact could be enormous.

I would love it if they asked experienced IRS leaders "what would a tax code look like such that you could effectively enforce and support it with half of your current workforce?" and then introduced legislation to implement such a radical simplification of the tax code.

But that would require a degree of cooperative capacity and political courage which this crew absolutely does not have.

Congressional "authorization" is actually a great example of government inefficiency. Our elected representatives spend months of negotiation and debate to come up with a number and then applaud themselves for doing so. But the process is totally meaningless, because they never actually appropriate the authorized amount.

The ultimate example of government efficiency would be deciding how much to spend on something (science, transportation, anything), putting someone in charge of spending the money and delivering the result, and getting out of the way.