It has been well over a year since Francis Collins announced his retirement as NIH Director. Since Dec. 20, 2021, his former deputy Larry Tabak has been serving as Acting Director—even though we are now long past the 210-day period during which a vacant position like this can be filled by an “acting” officer.

Why has there been no nomination for a permanent NIH Director? The White House has been playing this very close to the vest, but there are rumors that the conflict of interest and divestiture requirements might be an obstacle.

Whether or not that’s actually the case, let’s think about those requirements, which are found in 5 C.F.R. § 5501.109 and 5501.110. The rule is fairly straightforward: No “senior employee” (defined to include the NIH Director) or spouse can have any “financial interest in a substantially affected organization.” Such organizations include:

A biotechnology or pharmaceutical company; a medical device manufacturer; or a corporation, partnership, or other enterprise or entity significantly involved, directly or through subsidiaries, in the research, development, or manufacture of biotechnological, biostatistical, pharmaceutical, or medical devices, equipment, preparations, treatments, or products.

Makes sense, right? The NIH Director has the power to influence (even if not fully control) how billions of dollars of federal health funding are used. We wouldn’t want someone making such decisions out of personal financial interest.

But let me make an argument that is sure to be controversial:

These rules are overkill, and might do more to hurt biomedical research than to help.

Why do I say that? Some of the most successful and brilliant biomedical researchers end up developing a treatment, drug, device, etc., that they then patent and/or turn into a startup. Requiring them to divest would mean that they lose control of their investments or their company. It’s not a price that many would be willing to pay.

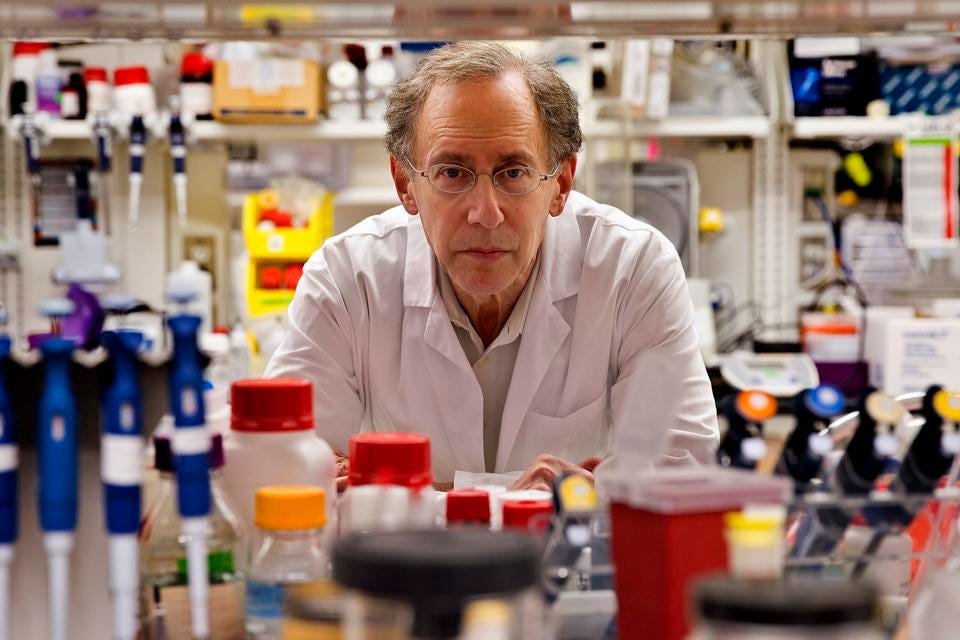

For example, take Robert Langer at MIT (here’s an article he contributed to the Good Science Project a while back). According to his Wikipedia entry, he runs the “largest biomedical engineering lab in the world,” has over 1,400 patents, and is the “most cited engineer in history.”

His net worth is estimated at $1.6 billion, due to all of the companies he has been involved with. He is a co-founder of Moderna, and his “patents have been licensed or sublicensed to over 400 pharmaceutical, chemical, biotechnology and medical device companies.”

If we could get someone like Langer to be the NIH Director—to be clear, he probably wouldn’t want that anyway!—that would be quite a coup.

But the current rules would require him to divest well over $1 billion. Why would he (or someone like him) do that for a position that pays a little over $200,000 a year?

We already have strong financial disclosure requirements (here is Francis Collins’ disclosure for 2021). We could add in a requirement to recuse oneself from any decision directly affecting a financial interest (e.g., if we made someone like Langer the NIH Director, and NIH partnered with Moderna, Langer would have to recuse himself from that arrangement).

Those requirements, coupled with public scrutiny and congressional oversight, should be sufficient. Otherwise, we are categorically ruling out some of the most prominent names in the biomedical field. It’s time to update the NIH/HHS conflict of interest rules to allow more of our nation’s top biomedical researchers to be eligible for NIH leadership.

I think you may be right that the rules should be relaxed, perhaps requiring senior employees to place their stocks in a blind trust or some other financial mechanism to distance them from their assets.

But I am skeptical that the Conflicts of Interest requirements are the real holdup of appointing a new director. Is there really no prominent scientist who would jump at the opportunity to direct the largest biomedical funder in the world?

I also wonder if eminent scientists, like Langer, are the best options for running these organizations. It seems like the role of director is more of administration and management, whereas a seasoned bureaucrat would also be a strong pick.

I'm speaking out of complete ignorance. The NIH organizational structure is foreign to me, but I think this is an interesting conversation about maintaining ethical standards in research while still encouraging good science.